'In many ways the 'Spiritual But Not Religious' outlook appears as an outgrowth of affluent western consumer culture: it has a strong element of the modern therapeutic search for personal wellbeing and security and tends towards a rather individualistic, inward-looking and self-serving attitude.'

What I’ve been arguing is that if we want full, truthful answers to those questions, so as to be able to foster a real relationship with God and answer the call to holiness, we have to turn to the reliable sources of Divine Revelation - Scripture, Tradition and the Magisterium - to point the way.

The issue I’d like to raise now is: what happens when people don’t rely on what we know about God’s revelation of himself, when they resort to other sources of information - their own imagination, perhaps, or the general beliefs and values of contemporary culture?

A significant and perhaps growing minority of people today like to describe themselves as ‘SBNR’ - ‘Spiritual But Not Religious’ - a rather broad description which means different things to different people.

I recently read two interesting advertisements in a local shop window.

The recent ‘Sunday Assembly’ movement is another novel example of a kind of secular religiosity, supplying the spiritual needs of those who reject doctrinal commitments but seek meaning, inspiration and a sense of belonging to a community of values, if not of faith.[1]

The common thread for people who describe themselves as spiritual but not religious is usually a rejection of traditional religion, mainly, I think, because they dislike the idea of definite, binding beliefs and moral norms. They prefer the idea of a freer, more open-ended spiritual exploration.

Also, as possibly the above examples illustrate, for people who describe themselves as SBNR, spirituality is seen as a dimension of psychological and emotional development and an aspect of an overall lifestyle, which they’re in the process of constructing for themselves.

In many ways the SBNR outlook appears as an outgrowth of affluent western consumer culture: it has a strong element of the modern therapeutic search for personal wellbeing and security and tends towards a rather individualistic, inward-looking and self-serving attitude.

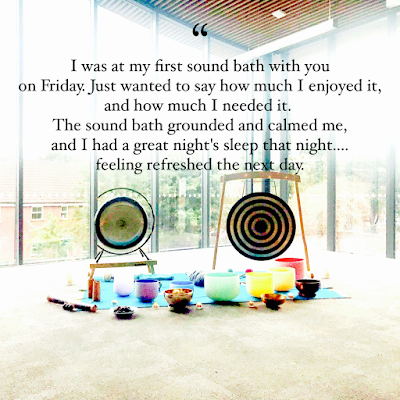

Feeling connected to the life-force of the universe, contemplating the beauties of nature, adopting a healthy diet and exercise regime, or even listening to Himalayan singing bowls, doesn’t move people very far beyond their own thoughts, needs and sensations.

Second, I think it has to be said that the Spiritual But Not Religious attitude tends to be naïve and superficial in relation to human sinfulness. SBNR individuals tend to see human nature as fundamentally good, rather than flawed, and to take rather a benevolent, complacent attitude towards themselves.

From the SBNR standpoint any ‘redemption’, any spiritual enlightenment or moral improvement, has to come from our purely natural and human resources. It can’t come from the extrinsic influence of God, his saving initiative through Christ, and the power of his supernatural grace, healing and perfecting our damaged nature.

The SBNR option does away with the whole business of having to relate to a Creator God with obedience and reverence. If anything, it gazes in the mirror and treats the potentialities of a self-contained human nature as ‘sacred’ and deserving of ‘reverence’ - or at least of celebration.

(ii) ‘Moral Therapeutic Deism’

Some years ago the American social scientists Christian Smith and Melinda Lundquist Denton made an extensive study of the religious views of teenagers and young people, not just Christians but Jews, Moslems and members of other faiths.[3]

The researchers conducted lengthy interviews with their subjects and found that although the young people came from very different religious traditions there was a marked convergence in their image of God and their understanding of the purpose of religious faith.

The authors labelled this view of religious faith ‘Moral Therapeutic Deism’ because of what they saw as its three main aspects:

The authors of the report summarised the young people’s opinions under five headings. They believed:

(1) that a God exists who created the world and who watches rather distantly over human life;

(2) that this God wants people to be good, nice and fair to each other, which they tended to see as being the core of all the different religions;

(3) that the central goal of life is to be happy and feel good about oneself;

(4) that God doesn’t need to be particularly involved in people’s lives except when they have problems that need to be solved; and

The authors concluded:

What I found interesting about this research is that I don’t think these views, or this idea of what religious faith is about, is restricted to American teenagers.

There’s quite a pronounced tendency among modern Christians, including Catholics, especially if they’re engaged in teaching catechism to children and young people, to be impatient with detailed beliefs about God and to downplay the reality of sin, the necessity of disciplined prayer, the moral demands of Christ’s teaching.

What they offer instead is a rather repetitive emphasis on ‘love’ - both in the sense of an undemanding, sentimental love on God’s part towards us, and in the sense of re-defining Christian love of neighbour to mean little more than showing a tolerant, inclusive and ‘non-judgemental’ attitude to each other, and/or championing subjects like social justice, minority rights and climate change.

Of course to say ‘God is love’ is to make an accurate statement. But God is a lot of other things as well, and modern Christians

[1] See Andrew Watts, ‘The church of self-worship: Sunday mornings with the

atheists’, The Spectator, 22nd February, 2014

(https://www.spectator.co.uk/2014/02/so-tell-me-about-your-faith-journey-sunday-morning-at-the-atheist-church) and, more favourably,

Andrew Brown, ‘The Sunday Assembly is not a revolt against God. It's a revolt against dogma’, The Guardian, 16th December, 2013 (https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/andrewbrown/2013/dec/16/sunday-assembly-revolt-god-dogma-atheist)

Also Adam Brereton, ‘My local “atheist church” is part of the long, inglorious march of gentrification’, The Guardian, 12th March, 2014 (https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/12/my-local-atheist-church-is-part-of-the-long-inglorious-march-of-gentrification).

It’s difficult not to see this conscious imitation of the structures and practices of organised religion as another instance of the way that, in a secular culture, the innate human hunger for God doesn’t disappear, but redirects itself into other, horizontal, channels.

[2] For many searchers after spiritual truth, including many Christian believers, an overemphasis on the Church’s institutional aspects can indeed constitute a genuine obstacle to their attempt to connect with God. Father Franz Jaliks expresses this concern well when he writes:

‘Now and then…people experience our organized religious structures as too complicated, impractical and artificial. Frequently these structures obstruct access to the divine. People are really looking for a simple, spontaneous, and immediate contact with God. Wherever I guided toward simplicity, immediacy and inner spiritual reality, people were relieved and told me that they had been looking in vain for this simple way for years or decades. Others confessed that they had encountered God secretly in this way without having the courage to say so, because of the fear of not being understood by their pastors.’Franz Jaliks

S.J., Contemplative Retreat, Xulon Press, 2003, p.3.

[3] Christian Smith with Melinda Lundquist Denton, Soul Searching, The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers, Oxford University Press, 2005.

4. Soul Searching, pp.163-164.

2 comments:

Well thank goodness the Pope doesn't think that everybody else is "naive, superficial, complacent, individualistic, inward-looking , self-serving etc etc etc". His Holiness has just stated that all religions lead to God.

I feel that the Pope, as quoted in the comment above, is right in saying "that all religions lead to God". Richard.

Post a Comment